Ethiopia’s education system expanded rapidly in the decades after the overthrow of the Derg in 1991. The net enrollment rate (NER) in elementary education, for instance, jumped from only 29 percent in 1989 to 86 percent in 2015, according to the UIS. Ethiopian government statistics report that the number of elementary schools tripled from 11,000 in 1996 to 32,048 in 2014, while the number of students enrolled in these schools surged from less than 3 million to more than 18 million. In secondary education, overall enrollment is much smaller, but growing modestly nevertheless: The NER in upper-secondary education grew from 16 percent in 1999 to 26 percent in 2015 (UIS).

The higher education sector, likewise, has come a long way since its humble beginnings. There were just three public universities, 16 colleges, and six research institutions in 1986 enrolling fewer than 18,000 students.[7] Today, there are 30 public universities, as well as a growing private sector. Ethiopia did not have a single privately owned tertiary institution before the early 1990s, but there are now 61 accredited private HEIs. The overall number of tertiary students in both public and private institutions exploded by more than 2,000 percent, from 34,000 in 1991 to 757,000 in 2014, per UIS data.

However, despite this expansion, Ethiopia still trails other LDCs in key education indicators. In fact, the rapid growth over the past decades has overburdened the system and created a slew of new problems, such as funding shortages and a deterioration of quality. Enormous progress in increasing access to education notwithstanding, some observers now consider the Ethiopian education system to be in a state of crisis, and that quantitative achievements in areas like elementary enrollments mask stagnation in terms of quality and learning outcomes.

Ethiopia’s adult literacy rate of 39 percent (2012), for example, is still one of the lowest in the world and far below the LDC average of 77 percent (in 2016, per UIS). Marked disparities in participation in education also persist between rural areas and urban centers, most notably Addis Ababa, as well as between low-income households and more affluent demographic groups, and between boys and girls. School drop-out rates are among the highest in the world: Just slightly more than 50 percent of enrolled children complete elementary education. Participation rates also fall off markedly at higher levels of schooling—Ethiopia’s upper-secondary NER remains fully 17 percentage points below the current LDC average (UIS).

In the tertiary sector, educational quality is strained by scarce funding, poor facilities and infrastructure, overcrowded classrooms, insufficient levels of academic preparedness among students, and a shortage of qualified teaching staff. Only 15 percent of university instructors had doctoral degrees in 2015. Many students were taught by young, inexperienced instructors holding just a bachelor’s degree. Research funding and outputs are consequently very low, so that Ethiopia ranks below other African countries like Rwanda, Senegal, Tanzania, or Uganda in comparative studies that measure research and innovation, such as the Global Innovation Index.

High and growing unemployment among Ethiopian university graduates, meanwhile, raises questions about the quality and relevance of academic curricula, which are considered ill-suited for current labor market demands. There are also great disparities in quality between public universities and a growing number of smaller private for-profit providers, many of them said to be of dubious quality. Former Prime Minister Meles Zenawi in 2010 went as far as accusing private HEIs of “not only providing substandard education but ‘… practically just printing diplomas and certificates and handing them out.”[8]

Crucially, access to tertiary education in Ethiopia remains severely constrained: While participation rates in higher education now exceed those of other East African countries like Tanzania or Uganda, Ethiopia’s tertiary gross enrollment ratio of 8.1 percent (2014) is below the LDC average and less than half that of neighboring Sudan (UIS). Also, tertiary education in Ethiopia remains elitist. Participation rates are highly skewed toward men from financially well-off households; women made up only 30 percent of all tertiary students in 2014 (UIS).

International Student Mobility

Little information exists on international student mobility to and from Ethiopia. There are no publicly available statistics on inbound mobility, but it can be assumed that the number of international students in Ethiopia is small, given that the poverty-stricken, conflict-ridden country hardly has the reputation of an international study destination and does not have notable high-quality universities.

Nevertheless, the Ethiopian government and institutions like the World Bank incentivize students from sub-Saharan countries to study at institutions like Addis Ababa University with limited scholarship programs. It’s possible that substantial numbers of African students, particularly those from worse-off, neighboring countries like Somalia, are enrolled in Ethiopian higher education institutions (HEIs), but that’s speculative given the absence of concrete data. Addis Ababa University, Ethiopia’s flagship institution and largest university, enrolled only 120 international students in 2016. Mekelle University, another large public university, had 88 international students as of 2017.

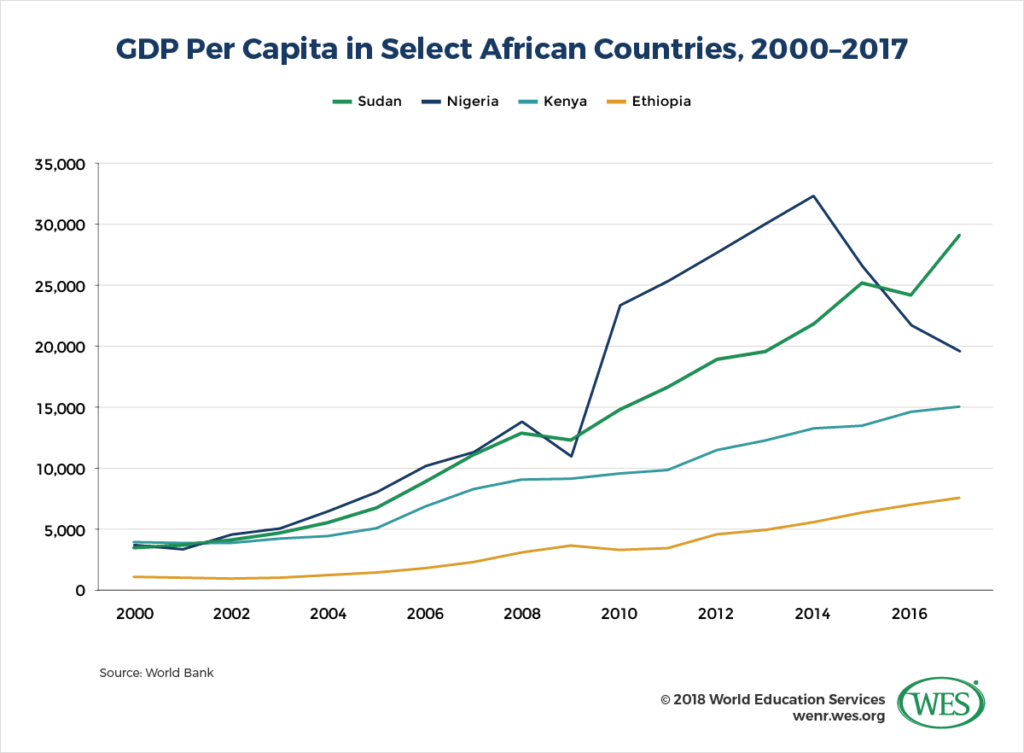

Outbound student flows from Ethiopia are small as well, if growing. As per the UNESCO Institute of Statistics (UIS), the number of Ethiopian students enrolled in degree programs abroad doubled from 3,003 in 1998 to 6,453 in 2017. To put this number into perspective, however, there are currently 89,094 Nigerians, 14,012 Kenyans, and 12,988 Sudanese studying in degree programs at foreign universities.

This gap is likely owed to a lack of disposable income in Ethiopia. Except for Nigeria, which has roughly twice as many tertiary students, Ethiopia has more tertiary students than both Kenya and Sudan and consequently a larger pool of potential international students. However, Ethiopia has a considerably lower per capita income and fewer middle-income households able to afford an overseas education. According to one survey of Ethiopian international students, a majority of them previously attended private and international secondary schools—a sign that they’re from affluent urban households. But even these students appear to be largely dependent on scholarship funding: 72 percent of surveyed students were on full scholarships and another 11 percent on partial stipends.